History of DeMoulin Antiques

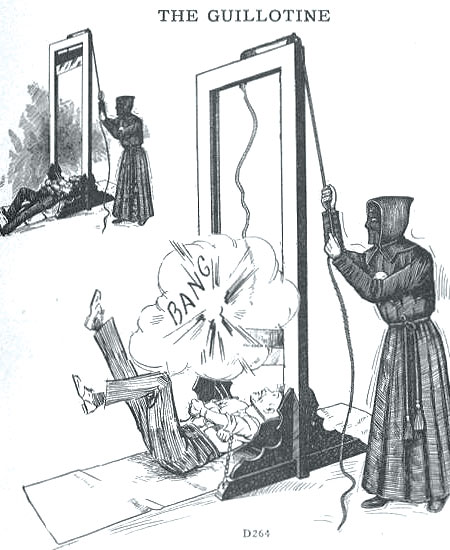

The fake guillotine was part of the hazing process by

some lodges, whereby cloaked men threatened inductees

with beheading unless they reveal organizational

secrets.

Imagine for a minute that it is 1900, and you have just

been admitted into the fraternal organization, the Modern

Woodmen of America (MWA). You have been a member

for almost a week, and you already know some of the

secrets and rituals that MWA members hold close to their

hearts. You approach the meeting hall to attend the next

assembly of members. After knocking on the door in a

secret rhythm, just as you were instructed, you begin to

recite the secret password. But, just before you can say the

word, four men open the door and drag you into the dark

interior of the building. They bind your hands and lower

you into a guillotine, and they begin to question you about

your organization’s secret rituals and passwords. After you

are interrogated for several minutes, your fellow Woodmen

burst into the room and chase off the imposters.

In all the commotion, you failed to notice the impossibly

bright red blood stain on the blade, the ridiculous costumes

the men were wearing, and the stopper that would have

inhibited the path of the blade…It’s just a joke. You passed

the test! The men around you shout their approval of your

accomplishment by saying, “Grand Officer, we present

you this candidate, whom we found a captive of outlaws,

and he was going to permit them to take his life rather than

reveal to them the secrets of this Order. We recommend

him to you as a worthy person for adoption into our

Order!

There is a good chance that DeMoulin Bros. & Company in Greenville, Illinois, supplied the prank guillotine and other similar devices all over America. Starting in 1892, DeMoulin Bros. pioneered and dictated an industry that has since faded away from American popular culture—fraternal lodge side-degree paraphernalia. Things that were considered “side-degree” were any ceremonies or rituals that were not sanctioned by the governing bodies of fraternal organizations. Someside-degree rituals were aimed at spicing up initiation ceremonies in order to bolster the lodge’s membership and improve meeting attendance. DeMoulin Bros. took on the challenge of inventing and supplying devices such as trick chairs and prank guillotines for these side-degree rituals and ceremonies.

Side-degree paraphernalia is a unique and interesting subject in its own right; however, studying DeMoulin Bros. reveals much more about American popular culture than just guillotines and trick chairs. It is revealed that side-degree paraphernalia and fraternal lodge expenses consumed a significant portion of late-Victorian household income. Males were the largest contributors to this industry, which challenges assumptions about male consumption patterns and exposes a movement away from a moderate Victorian lifestyle.

DeMoulin Bros. and Fraternalism

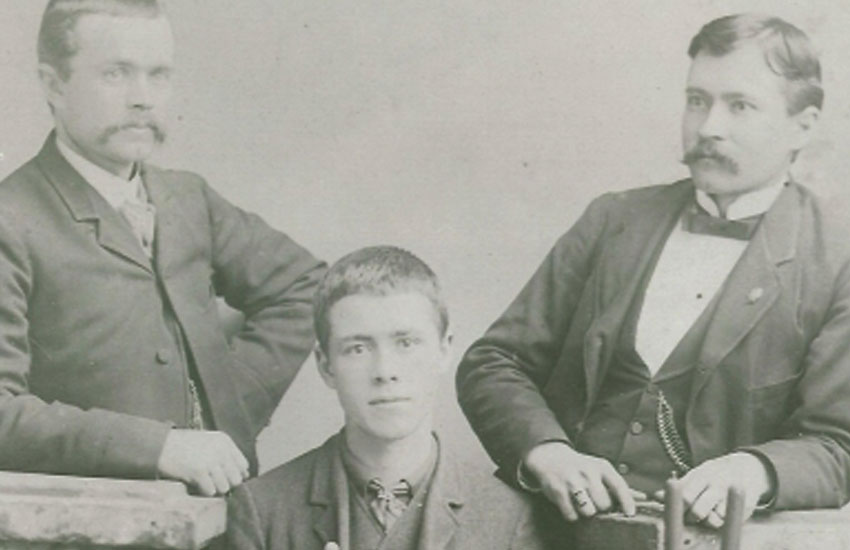

DeMoulin Bros., located in the town of Greenville, used many of the same manufacturing and advertising strategies as bigger companies. It sold unique and highly specialized products, and the owners of DeMoulin made millions doing it. The most accurate story about the conception of DeMoulin Bros. goes something like this:

In 1890, William A. Northcott, officer of the Venerable Counsel of the Modern Woodmen of America (MWA), approached Greenville businessman Ed DeMoulin with a business proposition. Northcott sought to increase the membership of the organization by employing DeMoulin to dream up and construct devices that made lodge initiation ceremonies more eventful. Northcott helped fund the operation from the start until Ed DeMoulin’s brother, Ulysses, purchased his shares. When this transaction took place, Ulysses demanded that Northcott throw in the contact names and addresses for the MWA camps as part of the deal. Ulysses suggested that if the list was gone when Northcott returned from lunch, nobody would blame him for its disappearance. The story ends with Northcott returning from lunch to find that Ulysses was gone, along with the list of MWA camps.

In its early years, the company was helped off the ground by local investors, but within a few years it was selling to multiple fraternal organizations all over the United States. The first large contract that DeMoulin Bros. received was in 1893, for 600 drill team axes for the Southern Illinois Modern Woodmen of America. In 1896, the company expanded its market nationally when it ordered 6,000 80-page catalogs and mailed them to each of the 4,500 MWA camps in America. Business was booming and the creative instincts of the DeMoulin brothers were supplying America’s obsession with fraternalism.

During the Golden Age of Fraternity, roughly 1870- 1920, an astounding one in five Americans belonged to fraternal organizations.3 This range of years has been assigned the title “Golden Age” because it represents the height of fraternal membership; and after this period, there was a sharp decline in the number of organizations and members. There are several sociological explanations for the growth of fraternalism in the United States. Walter Nichols’ 1917 study attributed this unification of men

into organizations to the human instinct for family and common welfare. Arthur Schlesinger posited the notion that Americans sought to form fraternal groups in an effort to create institutions apart from state and federal governments. Other scholars attribute their popularity with Americans to the cheap life insurance that many fraternal groups offered. More than likely, it was a combination of many factors that pushed Americans to join fraternal organizations in the nineteenth century.

Their purposes varied between reading poetry, singing, or providing safe havens for ethnic groups. Mostly, they formed a social environment for their members and provided financial aid to those in need. In 1999, Robert Putnam and Gerald Gamm conducted a study that incorporated 224 city directories from 26 citiesand towns. They created a list of 65,761 voluntary associations, of which 30 percent were fraternal or sororal, 28 percent religious, and the rest were strictly social, cultural, or political. The creation of these associations was a phenomenon encompassing both immigrants and nativists, and they existed within most belief systems, including Jews, Christians, and freethinkers, among others. Tocqueville’s view that “Americans of all ages, all stations in life, and all types of disposition are forever forming associations” accurately defines fraternalism throughout the nineteenth century.

Insurance was a major element of many fraternal organizations and certainly pushed Americans to jump on the fraternal bandwagon. The notion of common welfare was entrenched in fraternal societies since their creation. The most prominent mutual aid organizations by 1907 were groups such as the Ancient Order of United Workmen, Royal Arcanum, the Knights of Honor, and the Knights of Maccabees.

The social class component of fraternalism is one that has drawn several historians and sociologists to the subject. The impact that the Golden Age of Fraternity hadon class structure and social mobility can be narrowedto two broad avenues. In one way, many fraternal groups were egalitarian in that they did accept men and women from various social classes and professions. However, the second avenue for fraternal groups is that they often excluded certain races, ethnicities, professions, and age groups. It is completely appropriate to call fraternalism both egalitarian and socially exclusive. Some groups practiced a greater degree of exclusion than others

An impressive and colorful array of fraternal organizations was created in the latter half of the

nineteenth century. Freemasons and Odd Fellows were formed long before the creation of most other organizations, but many more sprouted up all over the United States: groups like Modern Woodmen of America (1883), Improved Order of Red Men (1834), Benevolent and Protective Order of Elks (1868), and many other groups with names associated with various types of wildlife, Biblical, and historical figures.

Fraternalism grew unimpeded in the latter half of thenineteenth century in urban and rural regions. Several companies were created for the sole purpose of supplying fraternal organizations with all that they needed to be fully equipped at meetings or out in public. Uniforms, badges, banners, and pins were an integral part of fraternal culture

and appearance. These items were a source of pride for the organizations and a way of advertising their lodge during parades and celebrations. Dr. William D. Moore wrote that there were businesses located in eastern states, but the largest supply firms devoted to the fraternal industry were located in the Midwest. In Gamm and Putnam’s massive fraternal study, they discovered that in 1910, small towns (average of 8,000 people) had 6.8 groups per 1,000 people

and big cities had around 3.2 groups per 1,000 people.11 Gamm and Putnam extolled the importance of studying rural fraternalism when they wrote, “After all, many more Americans at the turn of the century lived in Boises (1890 population, 2,311) than in Bostons (1890 population, 448,477)”

It is no surprise that the small town that raised the DeMoulin brothers undertook the task of spicing up fraternal lodge meetings. The location of these businesses is evidence of the popularity of fraternalism among rural Americans. M.C. Lilley in Ohio, Pettibone Brothers in Ohio, Henderson-Ames in Michigan, and Ward-Stilson in Indiana were a few of the biggest companies. DeMoulin Bros. was a minor participant in the fraternal supply industry overall, but its side-degree paraphernalia was unmatched in quality and inventiveness. is evidence of the popularity of fraternalism among rural Americans. M.C. Lilley in Ohio, Pettibone Brothers in Ohio, Henderson-Ames in Michigan, and Ward-Stilson in Indiana were a few of the biggest companies. DeMoulin Bros. was a minor participant in the fraternal supply industry overall, but its side-degree paraphernalia was unmatched in quality and inventiveness.

Side-Degree Paraphernalia and Male Consumption

“Side degree,” in The International Encyclopedia of Secret Societies & Fraternal Orders, is defined as an unofficial group existing within a fraternal organization. Side degree practices simply existed next to or beside the regular degrees of a given fraternal group. Tests of courage and dedication, just like the one described earlier, certainly

qualified as side degree behavior. Special interest groups involved in charitable or activist happenings that were not established by organization laws were also included

in the side degree designation. Buying devices for testing bravery and pranking materials added to the expenses of organizations and their members.

Male consumers in the late nineteenth century were generally overlooked, while their female counterparts were placed in the spotlight by advertisements. However, Mark A. Swiencicki wrote that a higher percent of late- nineteenth-century working-class household income went toward male rather than female consumption.14 In consumer reports from that time period, items like lodge paraphernalia, uniforms, workout gear, haircuts, shaves, and theater and saloon spending were not recorded as “consumer goods.”15 Swiencicki also looked at the percentage of ready-made clothing that was consumed by males in the late 1800s. In 1890, males consumed 71 percent of all ready-made clothing, and that does not include lodge uniforms or ceremonial costumes. He claimed that nearly 27 percent of working-class household disposable income went toward the husband’s social expenses.16 These findings show that working-class white men made up a larger percentage of consumer culture than their female counterparts, and a significant part of their expenses was attributed to lodge dues, the purchase of uniforms, and insurance premiums.

Working-class men made up nearly 35 percent of fraternal members, leaving nearly 65 percent of members to other social groups. These other groups also paid lodge dues, bought uniforms, and purchased lodge regalia. By the early 1900s, DeMoulin Bros. had a workforce that consisted mostly of women; the workers made a product that was almost entirely consumed by male lodge members. So much for the notion that women consumed goods while men created them. Fraternalism undoubtedly made up a large portion of total male consumption during the Golden Age of Fraternity. Lodge regalia and side-degree paraphernalia was a large industry that was supported by American men of various social classes, and DeMoulin Bros. was at the forefront of one of the most intriguing divisions of that industry

DeMoulin Bros.’ Side-Degree Paraphernalia DeMoulin Bros. exploded onto the scene of the fraternal supply industry in the late 1890s with its successful advertising methods and inventive lodge paraphernalia. As William Moore points out, most of the fraternal supply

companies offered basically the same products to a wide variety of organizations. Likewise, DeMoulin created specialized catalogs that were aimed at particular fraternal

organizations in the United States. This allowed it to offer similar products to multiple organizations with only a few unique items in each catalog.

Items that were unique to each organization included badges, banners, and uniforms. Typically, there was a uniform for every event an organization attended. For example, the MWA catalog from 1917 contained parade caps, gloves, leggings, buttons, and drill uniforms. The Woodmen were seen in their parade uniforms at fairs and Fourth of July celebrations all over the country in urban and rural settings. The Improved Order of Red Men catalog from 1911 enclosed several different varieties of stereotypical costumes such as Mohawk, Huron, Mohican, and Sioux. Also, unique to the Red Men catalog were

tomahawks, war clubs, totems, and wampum belts. In addition to the uniforms and regalia that were unique to each organization, side-degree paraphernalia was placed toward the back of each catalog. This is where DeMoulin Bros. excelled in the fraternal supply industry.